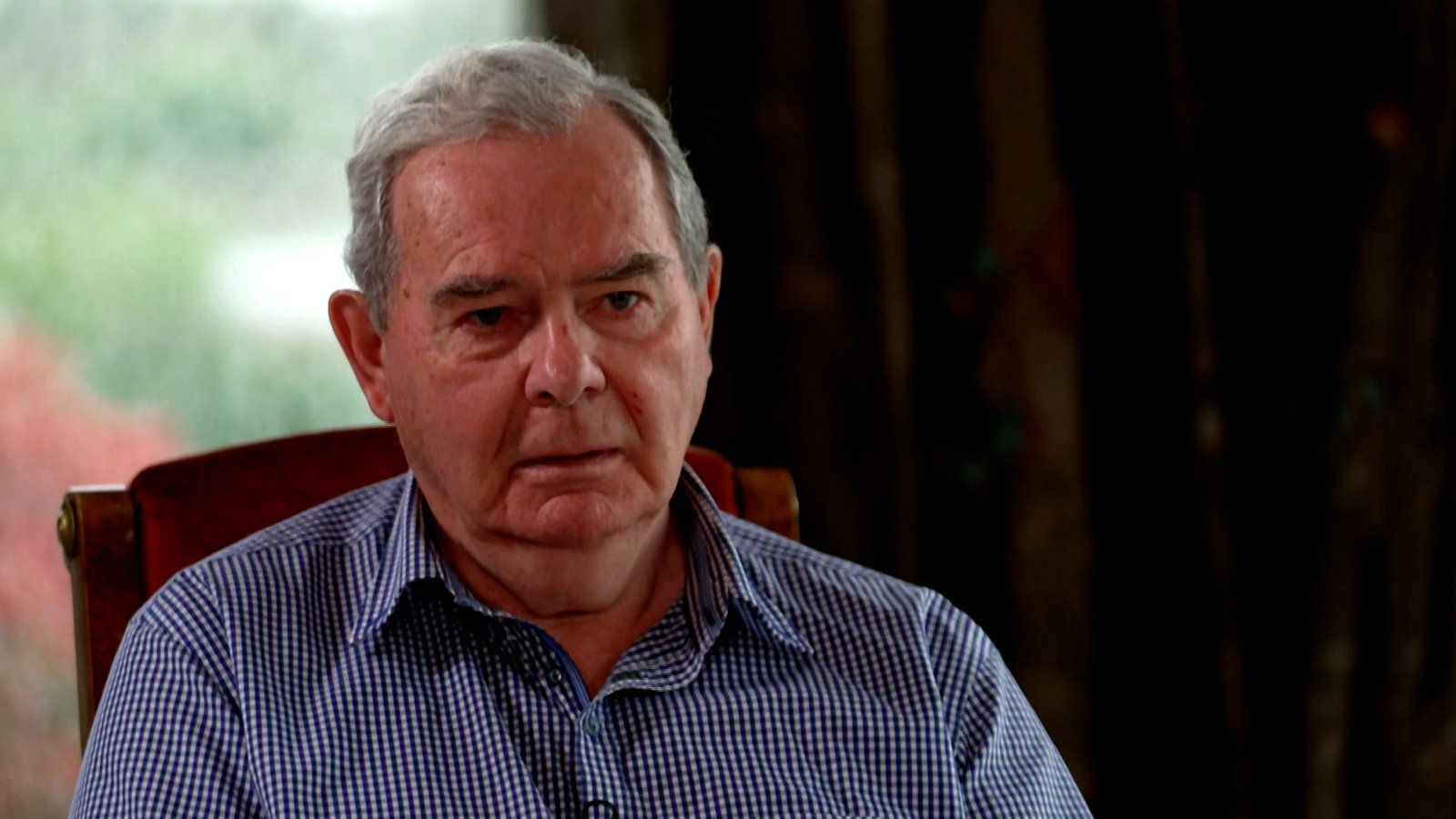

He was once Ireland’s richest man.

But Seán Quinn’s name is now synonymous with the worst judgement call in Irish corporate history, accusations about hiding assets and a warped campaign to regain control of his empire.

The jewel in the crown of his former business group has been sold to a Turkish building materials company – the final chapter in a saga of unbridled entrepreneurship gone awry.

The company which was sold, now called Mannok, employs 800 people in the supply of cement, concrete, quarry and insulation products to Ireland and the UK.

The Fermanagh-based group is highly successful with sales of over €300m last year. It is one of the most profitable parts of Quinn’s former empire.

The Turkish group Sabanci will buy out three US hedge funds which have held a 95% stake in the Irish company for the last decade.

A local management team, led by the Irish company’s new chief executive Dara O’Reilly and chief operating officer Kevin Lunney, will retain a 5% stake.

Three men were convicted of the assault. It was one of approximately 70 attacks on the business and its management team after Seán Quinn was ousted from his empire.

Quinn maintained he had nothing to do with the attacks or the assault on Mr Lunney.

He told RTÉ’s Quinn Country documentary “Why would I bother my head with Kevin Lunney? …I have nothing good to say about Kevin Lunney.”

But Seán Quinn was part of a public campaign to regain control of his businesses.

At its height, his group included pubs, hotels, glass, plastics, motor insurance, health insurance, cement, wind energy and insulation in Ireland, the UK and Europe.

He was very popular in the border counties which had traditionally been overlooked by multinationals, particularly during the Troubles.

In the eyes of many from the border region, he was one of very few people who built up a large successful business in the area and was providing jobs.

During the economic boom his business was valued at more than €4bn.

At the time shares in Ireland’s banks were soaring in value. Seán Quinn invested a massive €3bn in Anglo Irish Bank.

It was a huge gamble.

As the shares fell and other investors rushed for the exit, he kept buying, believing the shares were cheap and he was getting a bargain.

When the collapse came, stock in Anglo Irish Bank collapsed dramatically from €17 to 22 cent.

Not only had Seán Quinn invested heavily in the bank, but he was also one of its biggest customers, owing Anglo €2.8bn.

When the Quinn Group unravelled, the impact was enormous.

His motor insurance company Quinn Direct went into administration and needed to be rescued by the State’s Insurance Compensation Fund.

The fund needed millions as a result.

The Government imposed a 2% levy on all motor and home insurance products to pay for it.

That surcharge remains in place today and will be required for the next number of years.

The motor insurance business was sold to US group Liberty and is now owned by Italian company Generali.

Seán Quinn had properties and companies around the globe.

After the curtain came down on his businesses in 2012, Quinn and his son Seán Junior were jailed for contempt of court following allegations they had put assets beyond the reach of Anglo Irish Bank. The bank was still nursing huge losses.

In court Judge Elizabeth Dunne said the family’s behaviour was deceitful and blatantly dishonest.

She said they had taken every step possible to frustrate the bank.

Although he briefly returned to the Quinn Group as a consultant, Quinn fell out with management and left.

However, he continued his campaign to regain control of his businesses.

He claimed: “The level of betrayal is probably unprecedented in the history of the State.”

Others disagreed.

Alan Dukes, who had been a director of Anglo Irish Bank, said: “There was a piece of him that just didn’t understand the ramifications of what he had done.”

Some might consider it was a case of wouldn’t understand, not didn’t understand.