BBC

BBCIn less than two weeks voters in the Republic of Ireland will elect a new government.

Each party will be hoping the electorate will entrust them with safeguarding the future of a currently buoyant economy.

There have never been more people in work, inflation has recently fallen below 1% and the government could afford a giveaway pre-election budget.

But what are the economic issues that people are thinking about as they go to the ballot box?

A recent poll carried out by the Irish Times and Ipsos asked people what issue will have the most influence on their vote.

The clear leader was the cost of living, nominated by 30% of respondents.

Founding any new business involves a certain amount of confidence in the economy.

For one small business owner, things are off to a good start.

James Molloy co-founded his cafe Brosef with his brother in the centre of Letterkenny, County Donegal, earlier this year.

“People don’t mind spending a bit more for a quality product and it is promising to see there’s a market for the brand,” he said.

However, other hospitality businesses suffered during the post-pandemic inflationary shock, which peaked at more than 9% at the end of 2022.

Earlier this month, Perry Street Market, which had three cafes in the Cork city area, shut with immediate effect.

Notices posted in the cafe windows said hospitality has faced “unprecedented challenges in recent years” and “these difficulties continue to intensify”.

‘No feelgood factor’

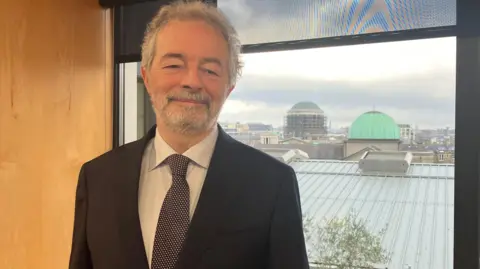

Economist Austin Hughes said households in Ireland are continuing to feel the lingering impact of inflation.

“Many are still finding it quite a strain to make it to the end of the month,” he said.

Mr Hughes runs a monthly consumer confidence survey for the Irish League of Credit Unions (ILCU).

His data suggests confidence has picked up over the last year but there is not “a pronounced feelgood factor”.

The ILCU’s chief executive Dave Malone said some of their data also points to how finances remain tight, with loans needed for household emergencies.

“We’ve issued more than 200,000 loans of less than €2,000 in the last 12 months and, of those, 50,000 were for less than €500,” he said.

“We have members coming into us, maybe a washing machine has broken down and they need finance to mitigate that challenge.”

Housing issues

The greatest financial challenge for many households remains the cost and availability of housing.

Data from the property listings website Daft.ie suggests that in the third quarter of this year advertised rents were up by more than 7% compared to the same time in 2023.

That took the average advertised national monthly rent to just under €2,000. In Dublin the average is closer to €2,400.

Rents have now been rising for 15 consecutive quarters as demand for housing has consistently outstripped supply.

The government has struggled to hit housing supply targets, partially due to historic underinvestment.

Director of the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Alan Barrett, said that in the aftermath of the country’s financial crisis in the late 2000s public investment was “cut back severely for a prolonged period of time”.

But then as the economy and population grew from the mid-2010s there was a widening infrastructure deficit.

“Our difficulty at the moment is we’ve lots of money to spend on infrastructure investment, we just don’t have the construction workers to deliver it,” Mr Barratt added.

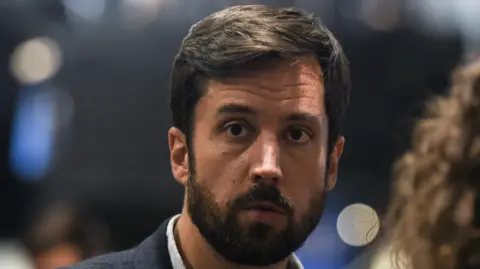

In theory this should be the biggest problem for Fine Gael, one of the two main coalition partners, which has been in government in one shape or form for the last 14 years.

The party’s case has not been helped by its former housing minister Eoghan Murphy, who used his memoir to criticise the party’s record.

“We didn’t escalate housing to priority number one – because we didn’t want to,” he told the Business Post newspaper.

“It was a choice we could have made.”

Back in Letterkenny there is a reminder that not everyone is sharing in Ireland’s prosperity.

Discretely tucked away behind some shops is the We Care foodbank, which has been operating in the town for the last 10 years.

“We help 80 to 100 families per week,” says Fintan McGrath.

He said the demand for their services has increased by 40% since 2021.

That’s not just about cost of living. It also reflects another big change in the country – immigration.

“When we started off the number of immigrants was way lower,” said Mr McGrath.

“We have the situation in Ukraine, people coming from Asia, South America. We give help to whoever comes through our door.”

Increased immigration is a mark of Ireland’s economic success. But how that has been managed is another election issue.