Chris Andrews,BBC News NI

Belfast Telegraph

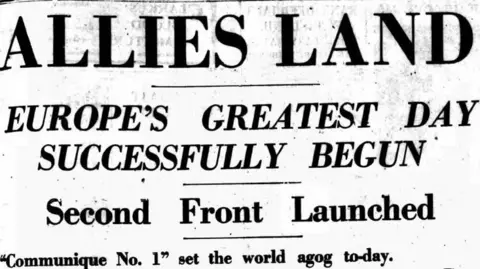

Belfast TelegraphCommunique No. 1 set the world agog.

On 6 June 1944, hours after the Normandy landings had begun, a late edition of the Belfast Telegraph declared it was “Europe’s greatest day”.

That morning listeners to the BBC Home Service were informed of a statement from the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF).

It told them that Allied armies had landed in northern France.

“In this brief manner the United Nations, their enemies, and the peoples of neutral nations, were told that ‘The Day’ had arrived,” the Belfast Telegraph reported.

‘Invasion going well’

Eighty years later, D-Day is still being remembered for its significance in world history and as a turning point in the allies’ fightback against Nazi Germany.

On 6 June 2024, some of the few remaining veterans will stand in commemoration with the leaders of a world they helped to shape.

The day after D-Day, 7 June, more information was being relayed to anxious families in towns and villages across Ireland.

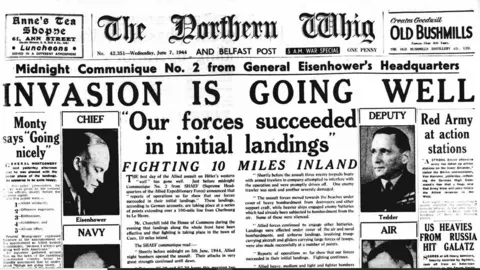

The Northern Whig, no longer in circulation, carried the headline ‘invasion is going well’ in its 05:00 war special issue.

Beside the image of SHAEF head Dwight D Eisenhower, the one penny paper reported forces had been successful in their initial landings.

This had come from communique No.2.

The Irish News

The Irish NewsEisenhower had been a familiar sight in Northern Ireland during the preceding months, rallying troops ahead of their deployment.

Fighting by 7 June, The Irish News detailed, was continuing 10 miles inland at Caen but there were “losses less than anticipated”.

It also reflected the Soviet advance on Germany to the east.

Under the section ‘news flashed round world’, the Irish News commented that D-Day was “the biggest news day the world has seen since the war began”.

News Letter

News LetterThe Belfast News Letter, the day after the invasion, carried a message from the speakers of the Northern Ireland House of Commons and Senate which conveyed to General Eisenhower their “heartfelt wishes for the speedy success of the immense and vital operations in which you are at present engaged”.

It also featured Northern Ireland’s prime minister, Sir Basil Brooke, appealing to workers that they redouble their efforts “to supply all the munitions and equipment that will be needed until the day of triumph dawns”.

For many people in Northern Ireland, the newspaper dispatches offered a glimpse of what their loved ones were living through and why their work on the home front mattered.

After years of war this would have felt like progress.

Derry Journal

Derry JournalIt was also common that news about the war was surrounded by advertisements for firms such as Ulster Creameries and Gallaher’s tobacco, with tradespeople offering their services and shows promoted at the Grand Opera House.

The News Letter’s front page was adorned with adverts, such was its format at the time, with Normandy coverage only appearing inside.

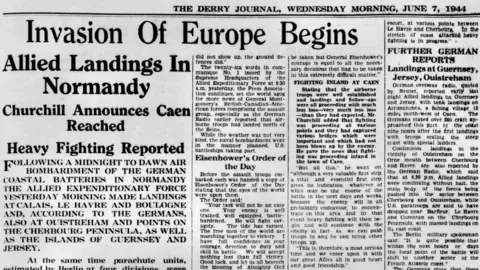

It was page three of The Derry Journal where readers learned the ‘invasion of Europe begins’.

It also referenced developments in Rome which had just been liberated.

Vatican Radio, it highlighted, reported the largest crowd in living memory in St Peter’s Square “clamouring for the Pope”, who made a speech that “Rome had been saved the horrors of war by both belligerents”.

‘Excited crowds’

Italy, north Africa, and other fields of war involving Northern Ireland service personnel remained under the spotlight despite the breaking news from France.

On D-Day, for instance, the News Letter reported that the family of Flying Officer WA Lawrence Colhoun, a former Methodist College rugby captain, had been officially informed of his death.

He had been reported missing three months earlier after a raid over the German city Nuremberg.

Such memories of bombing raids would have remained raw in Northern Ireland after the Blitz.

A reminder of this can be seen in the top masthead of the Belfast Telegraph which informed readers of the black-out times to abide by.

The Irish Times

The Irish TimesThe Irish Times’ 7 June edition reported on the world reaction a day into the invasion, sharing a Reuters report that speeches by Winston Churchill and Eisenhower had been carried in full on Moscow radio.

The Dublin-based newspaper also showed maps of the English channel and a detailed guide to Normandy where landings were happening “constantly”.

“In neutral capitals excited crowds bought up special editions of newspapers,” it reported.

Reflecting on those headlines today reveals a moment of great excitement but also uncertainty about a war which was far from over.