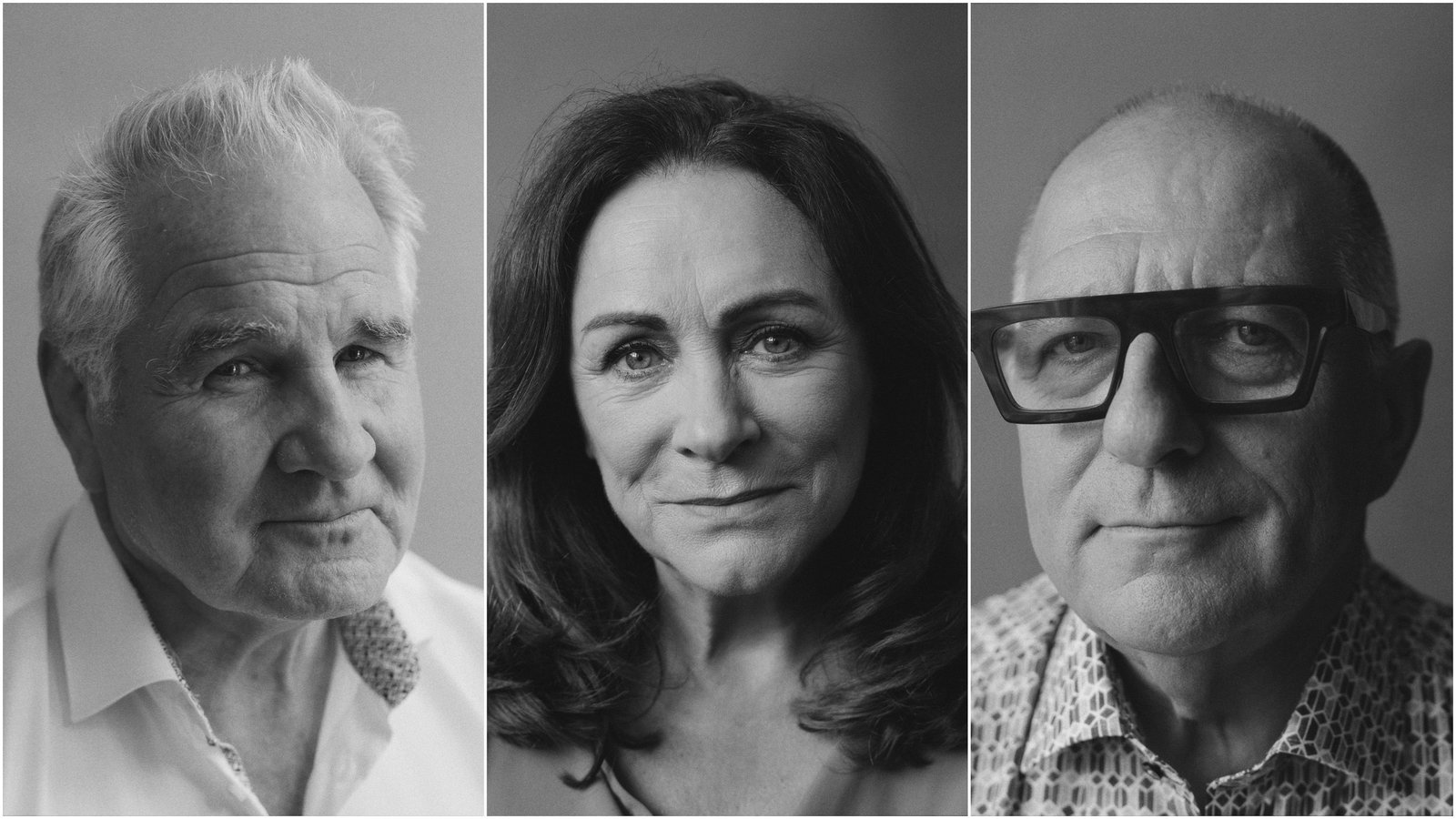

You will know many of the faces that are represented in the ‘Hope In Focus’ portrait exhibition that has opened in Dublin’s Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts for World Mental Health Day.

Among them are Olympian and sports reporter David Gillick, architect and presenter Hugh Wallace, singer Mary Black, rugby pundit and children’s book author Brent Pope, and teacher, author and presenter Emer O’Neill.

Others in the exhibition may be less used to the limelight – they are the Aware volunteers.

It is a diverse group, but there is something they all have in common, each of them has experienced depression.

“Depression is a widespread and often misunderstood condition that can affect people from all walks of life,” said Dr Susan Brannick, Clinical Director at Aware.

The purpose of the exhibition, she said, was to “shine a light on both the shared and the unique aspects of the experience of depression and how we can talk to each other about what is a common yet often misunderstood human experience”.

According to Aware’s 2024 national survey, one in five respondents had been diagnosed with depression.

But the number of people who thought they had experienced depression, but where it went undiagnosed, was much higher at 53%.

The survey also found that stigma remained an issue.

Almost half of those who said they had delayed accessing mental health supports cited “shame, embarrassment or fear of judgement” as the reason why.

“On the flip side of that, however, we did find that the people who did reach out for help found it useful,” Dr Brannick said.

For example 83% of those who attended a GP and 79% of those who attended a psychiatrist believed the care they received “definitely” or “to some extent” met their mental health needs.

“For many it was that first step in that journey of recovery,” Dr Brannick said.

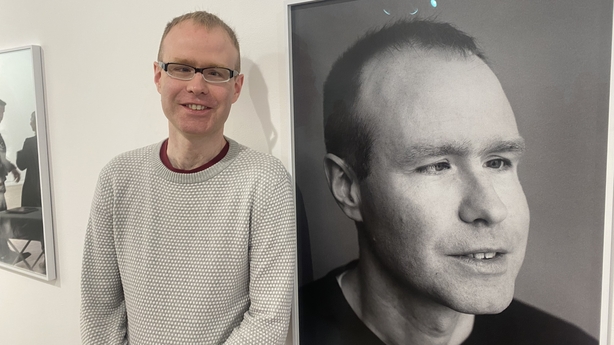

Standing in front of his portrait, Olympian David Gillick told RTÉ News about his experiences of anxiety and depression and his journey towards improving his own mental health.

“I think coming from sport and particularly being male, there is that stigma around asking for help and advice,” he said.

“I come from a sport where it is faster, fitter, stronger, show no weakness, that kind of alpha male syndrome, where the easiest thing to do is say nothing,” the two-time European indoor champion and Irish 400m record holder said.

“When my career ended, you’re kind of thinking, who am I know? Where’s my identity? What’s my purpose? And you’re struggling for routine,” he said.

“Through open communication and professional support I have learnt an awful lot about myself, and I can spot the little triggers, (I have) a little awareness, I can go okay, how am I feeling now? I can check in with myself,” Mr Gillick said.

“I have a little bit of a tool box, simple practical things that I do to keep me on the straight and narrow, I think that’s really important.”

Emer O’Neill is outspoken on many issues close to her heart, but she admitted that it can still be daunting to speak out about metal health.

“It’s difficult because people see it as a vulnerability, they see it as a weakness, and I’ve just decided in myself that it is not a weakness of mine, it’s me, it’s a part of me,” the author and presenter said.

Ms O’Neill has experienced post-natal depression after the births of each of her three children.

“We need to talk more about post-natal depression, because as women sometimes we are just expected to get up and go, ‘ah you’ll be grand’, like I went back to work seven days after having my daughter which is ridiculous, and my mental health really suffered from that.

“We are not superheroes, we are humans and we need to be kind to ourselves,” Ms O’Neill said.

“When you are giving pieces of yourself, when you are not fully whole yourself, that’s where you get into burnout and the mind can be a dangerous place,” she said.

Last year Ms O’Neill was also was diagnosed with autism and ADHD.

“It’s taken a year to really digest that, stages of: “no-way, its not true” to “yes that makes all the sense”, to sadness, to anger, to rebirth and finding out who I am,” Ms O’Neill said.

“Because something along with autism and ADHD can be a lot of masking and trying to fit in to social situations and learning behaviours from others, so you have to do a step back, and go: ‘Who am I?’

“I’m okay with who I am but it has been a very long journey to get there and I suppose my advice to people is: maybe just take that first step to talk about it,” Ms O’Neill said.

Volunteer Cathal Joyce’s face is also among those captured in black and white on the wall.

He began volunteering with Aware’s support groups and phoneline 18 months ago.

“I think what drew me into it was I had a lifetime with my own experiences where at different times I struggled to be motivated and struggled to enjoy life, and then at other times I was very well,” he said.

“A lot of the time what you really need is somebody just to listen,” Mr Joyce said.

“For a long time I was afraid to admit I had problems with my mental health, I was ashamed by it, I was embarrassed by it,” Mr Joyce said.

He described how he is no longer being afraid to speak about his mental health and how this formed part of his recovery.

“It can affect anybody at any time in any circumstance and you’re not alone, and I think for a long time I felt alone because I didn’t want to tell anybody. But now I don’t feel that need to hide it anymore.”

The exhibition will be open to the public from 10 until 13 October.