Eibhlis Gale-Coleman

Eibhlis Gale-ColemanStrokestown was a welcome reprieve after our three-hour coach ride from Dublin, predominantly bending through winding country lanes. The small town in Roscommon, Ireland’s central bog county, has a “one-horse” feel; its popular pub, J Beirne, is accessed through a simply labelled, plain white door in the back of a grocery store. A 2022 census cited a total population of just 850. However, Strokestown is not just a small community in rural Ireland – it’s the trailhead for a trek commemorating the most tragic walk in Irish history.

My father and I had come here to hike the National Famine Way, a 165km heritage trail that connects Strokestown with the shoreside capital of Dublin. The route, dotted with bronze shoe trail markers, was launched in 2020 to commemorate 1,490 Strokestown residents who made this same journey on foot in 1847 after being forced out by their Anglo-Irish landlord, Major Denis Mahon. Failing to pay rent while starving under a national famine, they struck a deal to walk to Dublin in exchange for free passage to Canada – an agreement to undergo “assisted” emigration. Many would perish and lose contact with their families for generations to come, gaining them the nickname “the missing 1,490”.

The trail is walkable in a minimum of six days to keep daily mileage feasible and allow time for sightseeing along the way. It is positioned between two poignant attractions: the National Famine Museum and the EPIC Museum of Irish Emigration. While sombre, it’s an immense trek of education, connection and heritage. Increasingly hailed as “Ireland’s Camino“, the National Famine Way addresses the role that starvation and forced emigration played in shaping the modern Irish diaspora. It also shows that the missing 1,490 who tackled the walk to Dublin are far more than just a statistic; the trail hopes to reiterate that their memory should not be forgotten.

The event occurred during the Irish Famine (An Gorta Mór) that followed a catastrophic potato blight. The impact stretched from 1845 until 1852, damaging 75% of crops andespecially endangering tenant farmers whose primary food source and income came from potatoes.

Alamy

Alamy“There was a quarter of the population surviving on potatoes,” said Caroilin Callery, a prominent figure behind the trail’s creation and the daughter of Jim Callery, who founded the National Famine Museum after finding more than 50,000 local famine documents, including an 1846 petition from starving tenants in Cloonahee begging for assistance. Now a director of the Irish Heritage Trust, she explained: “An acre of land could give you enough potatoes to survive and have your family survive, and Irish people were known to be eating up to 16lb of potatoes a day.”

SLOWCOMOTION

Slowcomotion is a BBC Travel series that celebrates slow, self-propelled travel and invites readers to get outside and reconnect with the world in a safe and sustainable way.

“In or around £10m between 1845 and 1852 was spent by the British government in various kinds of schemes in Ireland and little more than 10 years later there was £64m spent on the Crimean War,” said Callery, noting the deprioritisation of saving those lower Irish classes.

One such scheme was relocating civilians to the New World. This emigration strategy reduced the population in Ireland while reclaiming the indebted rental properties that were no longer profitable for the predominantly Anglo-Irish landlords.

Strokestown experienced one of the largest assisted emigrations in Ireland. The small town was centred around the privately owned house and grounds of Strokestown Park Estate, where the adjoining National Famine Museum now resides. Mahon inherited the estate in 1845, with the property already saddled with £30,000 in debt and tenant farmers who’d missed payment after payment. By 1847, he’d secured court rights to evict these families, offering three options: homelessness; the workhouse; or assisted emigration to Canada.

National Famine Museum

National Famine MuseumCanada came with a catch, however; the passage would be paid for by Mahon, but the tenants had to walk 165km through unwelcoming terrain, exposed to angered wanderers, thieves, mobs and all elements to reach the ships in Dublin. Already starving and often dragging small children in tow, this was an agonising feat to demand.

The National Famine Way not only follows their route, but has a poignant stance in partnering with scholars to trace the original individuals who made the journey. In 2013, Strokestown even welcomed the grandson of Daniel Tighe, a 12-year-old boy who survived the journey on foot and boat, carving out a new life in Canada. The entire town burst into celebration on his descendent’s arrival, who’d been discovered by sheer luck through investigations in Canada.

My father and hiked the trail in August, and on day one of six, our feet were already starting to throb as we walked 15km from Strokestown to Cloondara, the starting point of the Royal Canal. Just like the original walkers, arriving in Cloondara marked the beginning of our real journey. The canal would have been the most direct route to Dublin in the 19th Century, a rammed chaos of muddled passengers and freight transportation.

The initial 32km stretch snaked alongside the waterway from Cloondara to Abbeyshrule. The scenery stayed much the same as we strolled past meadows and counted down the canal’s black-and-white-painted locks. Opening the National Famine Way app, I browsed through audio files for each section of the walk, which contained stories on some of those who braved this journey and area-specific historical insights.

Eibhlis Gale-Coleman

Eibhlis Gale-ColemanI listened to the haunting audio rendition of Daniel Tighe’s distress at leaving behind the homely sight of Sliabh Ban, Roscommon’s tallest hill. Near Mosstown Harbour, the lilting youth’s voice continued with a disturbing tale of crazed, starving dogs fighting over a human corpse they’d pulled from a field. By the time we were an hour outside of Abbeyshrule, the first few blisters were rearing their unwanted heads. I gingerly applied plasters, wondering how the 1847 walkers got by lining their shoes with moss, as I’d earlier learned on the app.

There were no hotel rooms available in Mullingar, pushing us out to the next village of Moyvalley and creating a 40km beast of around nine hours rather than the recommended 30.3km. The canal was serene, with wildflowers and bullrushes swaying at eye level, disrupted only by intermittent splatters of rain or a startled heron. The original walkers would have set up camp along these banks. But, following in their footsteps, the scarce hotels were a reminder of the isolation and true scale of the journey.

The road surface switched between asphalt and tarmac, with the Mullingar workhouse and famine graveyard providing respite from our trudge. The 1841-built institution, which gave housing and employment to the desperate, is still relatively intact, although its cemetery stands testament to its inefficiency as a safe refuge in its time; a lingering home for the people from the period who didn’t make it. The workhouse complex was ridden with disease due to overcrowding, and it’s thought that the graves would have extended far beyond their modern boundaries.

Maynooth was our final overnight stay, a bubbly university town with castle ruins and ornate architecture. The final stretch of the trail was the hardest; my feet were so blistered that even hobbling to the shower the night before had felt like a battle. At 05:00, unable to sleep with adrenaline pumping, we set out on an early start. I couldn’t tell if it was the exhaustion of walking more than 130km or the sudden dawning of the gravity of the tragedy, but I spent much of it in tears. Rested and fed, it was unfathomable to even begin to process how starving civilians, including children and the elderly, had traversed an identical route, not knowing what their future held.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFinally emerging at Dublin’s River Liffey, we were beaming. But I couldn’t have finished the National Famine Way without my dad. It’s the quiet ways that parents selflessly make your life easier. Silently sneaking the heavier bags, offering the last sips of water and getting your order in first when you finally reach somewhere serving food.

It was heartbreaking to think of the love that Mary Tighe, Daniel’s widowed mother, would have had for her children. Perhaps she, too, took the heavier bags as they walked and stood aside to prioritise food and water for them. Yet Dublin represented a different kind of finality to her journey, and her 12-year-old son would next touch land in Canada as an orphan, accompanied only by the responsibility of becoming a sole carer to his younger sister.

HOW TO WALK THE TRAIL:

The 165km trail starts from the National Famine Museum on Strokestown Park Estate, ending at the River Liffey in Dublin, from where you can walk an additional 500m to collect a certificate from the EPIC Museum. It takes a minimum of six days to walk; allow longer to add leisurely detours to attractions like Mullingar Workhouse, Corlea Trackway and ruins like Maynooth Castle. The free National Famine Way app is available on Android and Apple with audio guides and step-by-step historical insights.

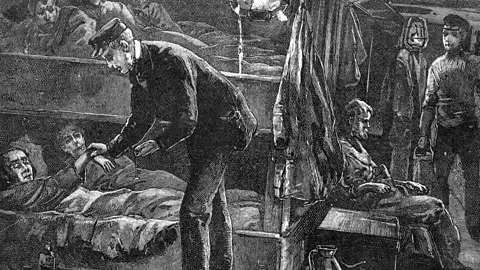

The survival of the transatlantic voyage was a whole new beast aboard the darkly nicknamed “coffin ships”. These often unseaworthy vessels were used to transport thousands of Irish emigrants across the Atlantic in the famine years. A third of the 1,490 would not see the new life they’d been promised.

“We were aware that these people had been very much forgotten,” Callery said of the 1,490.” There was a veil of silence over the famine from 1845 right through to the mid-1990s. It was rarely spoken about; it wasn’t covered in history in schools.”

It was agonising to me how a trail that was mostly tackled by families resulted in such traumatic fragmentation and loss. But I realised as I walked, the National Famine Way takes a bold yet sensitive approach to preserving what is part of Ireland’s darkest history.